Uric Acid Microspheres: Unexpected Architecture in Reptile Waste Reveals New Soft Matter Insights

Posted in ISM Stories News Story

A newly published study led by ISM member Prof. Jennifer Swift and collaborators, “Uric Acid Monohydrate Nanocrystals: An Adaptable Platform for Nitrogen and Salt Management in Reptiles,” explores the surprising nanostructure of uric acid waste produced by ball pythons. The work, which appeared recently in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, sheds light on how reptiles efficiently package and transport large quantities of this low-solubility metabolic material offering potential insights for tackling crystal-deposition diseases in humans. The study has already drawn significant attention, with coverage from more than 80 news outlets already.

Visualizing Uric Acid Architecture

Image Title: Uric Acid Microspheres

Image Credit: Alyssa Thornton

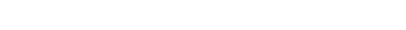

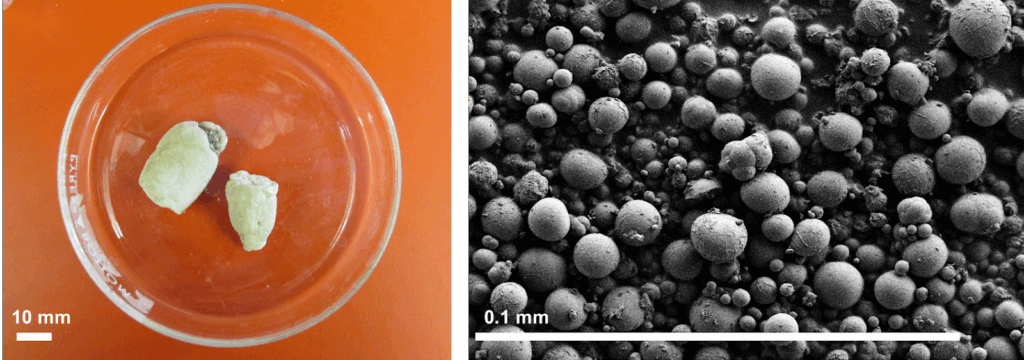

This month’s featured image presents ball python urates at two magnifications. A standard photograph (left) and a scanning electron micrograph (right) together reveal that snakes excrete nitrogen as solid, micron-sized spheres of uric acid. Higher-resolution imaging uncovered an unexpected twist: each sphere is composed of tightly packed nanocrystals. This surprising architecture opens new questions about how nature optimizes the storage and transport of insoluble materials.

Why It Matters

Uric acid is a natural metabolic product in many species but its low solubility makes it clinically significant in humans, where it can crystallize into gout deposits or kidney stones. Reptiles and birds, however, excrete uric acid in solid form without issue. Understanding how these animals safely assemble and manage crystalline waste offers a fascinating soft matter puzzle with potential biomedical implications.

Organic crystals like uric acid fall squarely within the domain of soft matter. This study reveals a previously unrecognized structural sophistication—nanoscale crystallites organized within microscale spheres—that may inspire new ways of thinking about crystal handling, biomineralization, or even therapeutic strategies for crystal-related diseases.

Research Challenges & Technical Innovation

Capturing the nanocrystalline architecture of the uric acid spheres required careful high-resolution imaging. While the microspheres themselves are easily visible, resolving the internal nanocrystals demanded advanced electron microscopy. The discovery that these spheres possess a hierarchical structure—nanocrystals forming micron-scale particles—was entirely unexpected and required confirmation across multiple imaging sessions and samples.

A Long-Term Collaboration

This work grew out of a collaboration sparked in 2019, when herpetologist Dr. Gordon Schuett (Chiricahua Desert Museum and Georgia State University) contacted Prof. Swift about puzzling differences in urate samples from genetically similar snakes in identical conditions. Together with Dr. Tim Fawcett, an expert in X-ray powder diffraction and former director of the International Centre for Diffraction Data, the team launched a sustained investigation into the composition and structure of reptile urates.

What began as a simple question, “why do these samples look so different?,” has become a multi-year research program revealing unexpected complexity in a system that had gone largely unstudied.

Looking Ahead

The team plans to continue exploring the formation pathways, structural variability, and transport properties of uric acid micro- and nanocrystals across species. Further work may help answer broader questions about crystal aggregation, biomolecular templating, and how nature evolves strategies for managing insoluble metabolic waste.

Inspiration Behind the Research

Prof. Swift has studied uric acid crystals for more than 25 years, fascinated by their diverse compositions and structures. The opportunity to investigate natural reptile urates which was made possible through Dr. Schuett’s outreach opened a new chapter for fascination. “I didn’t have a good answer at the time,” she recalls. “So I asked him to send some samples. That simple step grew into a wonderful long-term collaboration and a project full of surprises.”

Read the full publication in Journal of the American Chemical Society: HERE